Introduction

For centuries, Christians have confessed that in the Eucharist, they receive not merely bread and wine, but the true Body and Blood of Jesus Christ. This doctrine—known as the Real Presence—stands at the very heart of Christian worship and has been the consistent teaching of the Church from its earliest days. The phrase "the Eucharist" comes from the Didache, an early collection of the apostles' teachings, and has been used in the Church from the start.

This treatise presents a comprehensive case for the Real Presence and the theological understanding of transubstantiation by tracing three interconnected lines of evidence:

- Scriptural Foundation: From Old Testament prefigurements to Christ's explicit teaching in John 6 and the institution at the Last Supper

- Apostolic Witness: The unbroken testimony of the Church Fathers from the first century through 1517 AD

- Doctrinal Development: The organic growth from lived practice to theological precision in the doctrine of transubstantiation

"For my flesh is true food, and my blood is true drink. He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him." — John 6:55-56

.jpg)

Raphael, Disputation of the Holy Sacrament (c. 1509-1510)

The Eucharist Foreshadowed: Old Testament Types

1. Melchizedek's Bread and Wine

"And Melchizedek king of Salem brought out bread and wine. He was priest of God Most High." — Genesis 14:18

The first prefigurement appears in Genesis with Melchizedek, the priest-king who offers bread and wine to bless Abraham. This mysterious figure becomes crucial in the New Testament, where Christ is identified as a priest forever "in the order of Melchizedek" (Hebrews 7:17).

The Connection: The Levitical priesthood offered animal sacrifices. Christ's priesthood, following Melchizedek's order, offers bread and wine—establishing the form of the Eucharistic sacrifice from the very beginning of Scripture.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Meeting of Abraham and Melchizedek (c. 1626)

2. The Manna in the Wilderness

"And the people of Israel ate the manna forty years... till they came to the border of the land of Canaan." — Exodus 16:35

For forty years, God miraculously fed Israel with "bread from heaven"—a supernatural food that appeared with the dew each morning. First-century Jews widely expected the Messiah to provide this manna again.

The Greater Reality: Jesus explicitly identifies Himself as the true bread from heaven in John 6. But notice the "greater than" logic: If the type (manna) was miraculous physical food sustaining bodily life temporarily, the antitype (Eucharist) must be something far greater—supernatural food bestowing eternal life. A mere symbol would be less than the manna, not greater.

Nicolas Poussin, The Gathering of Manna (c. 1637-1639)

3. The Bread of the Presence

"You shall set the bread of the Presence on the table before me regularly." — Exodus 25:30

In the Temple, twelve loaves of sacred bread (Hebrew: Lechem haPanim—"Bread of the Face") were perpetually kept before God. This was considered "most holy," a continual covenant offering consumed only by priests.

The Fulfillment: Jewish tradition tells us priests would elevate this bread before pilgrims declaring, "Behold, God's love for you!" The Eucharist fulfills this perfectly—the perpetual presence of Christ in the tabernacle, elevated at Mass, consumed by the royal priesthood of believers.

4. The Passover Lamb

"Tell the whole congregation of Israel that on the tenth of this month they are to take a lamb for each family, a lamb for each household. If a household is too small for a whole lamb, it shall join its closest neighbor in obtaining one; the lamb shall be divided in proportion to the number of people who eat of it. Your lamb shall be without blemish, a year-old male; you may take it from the sheep or from the goats... They shall take some of the blood and put it on the two doorposts and the lintel of the houses in which they eat it. They shall eat the lamb that same night... You shall let none of it remain until the morning; anything that remains until the morning you shall burn... The blood shall be a sign for you on the houses where you live: when I see the blood, I will pass over you, and no plague shall destroy you when I strike the land of Egypt." — Exodus 12:3-5, 7, 8a, 10, 13

"This day will be a day of remembrance for you, which your future generations will celebrate with pilgrimage to the LORD; you will celebrate it as a statute forever." — Exodus 12:14

The original Passover required an unblemished lamb whose blood, applied to the doorposts, saved Israel from death. But the sacrifice wasn't complete with the lamb's death—God commanded the flesh must be eaten by the covenant family. The instructions are remarkably specific and reveal profound theological principles.

Critically, God declares this Passover meal to be "a day of remembrance" that future generations must celebrate "as a statute forever." The Hebrew word for remembrance (zikkaron) carries far more weight than mere mental recollection—it signifies a liturgical memorial that makes the past salvific event present again. When Israel celebrated Passover in subsequent generations, they weren't simply thinking about the Exodus; they were participating in it anew, as if they themselves had been delivered from Egypt. This is the biblical pattern for liturgical memorial: not a mere reminder of what happened once, but a making-present of God's saving action.

The Eucharistic Connection: When Jesus institutes the New Covenant memorial at the Last Supper—itself a Passover meal—He uses identical language: "Do this in remembrance (anamnesis) of me" (Luke 22:19). The Greek anamnesis parallels the Hebrew zikkaron, signifying the same liturgical reality: not merely recalling the past, but making Christ's once-for-all sacrifice on Calvary sacramentally present in the celebration. Just as eating the Passover lamb made Israel's deliverance present across generations, so eating Christ's Body and drinking His Blood makes His redemptive sacrifice present to us. This is why the Church has always understood the Eucharist as both memorial and real presence—the memorial is real precisely because Christ Himself becomes present through the liturgical action. A symbolic memorial could not fulfill the biblical pattern established in Exodus 12:14; only the Real Presence makes the Eucharist the true "statute forever" that brings Christ's saving death to every generation.

Notice God's concern that the lamb be properly proportioned to the household: "If a household is too small for a whole lamb, it shall join its closest neighbor in obtaining one; the lamb shall be divided in proportion to the number of people who eat of it." This wasn't merely practical advice—it ensured complete consumption. The command continues: "You shall let none of it remain until the morning; anything that remains until the morning you shall burn." Why this emphasis on total consumption? Because the lamb's saving power wasn't accessed through its death alone, but through eating its flesh. The blood on the doorposts marked participation in the covenant, but eating the lamb unified the family as covenant members.

This establishes a pattern that echoes through Scripture: covenant participation requires consumption of the sacrifice. The family was to size the lamb correctly so that nothing remained—every bit was to be consumed by the covenant community that very night. What couldn't be eaten was burned, never left to decay, for this was holy food that mediated God's saving action.

The Pattern Established: This creates a biblical principle: participation in covenant sacrifice requires physical consumption of the victim. The careful sizing of the lamb, the mandate for complete consumption, the prohibition against letting it remain until morning—all emphasize that the sacrifice is completed not just by death and blood, but by eating. St. Paul explicitly calls Christ "our paschal lamb" (1 Corinthians 5:7). Therefore, when Jesus institutes the memorial of His sacrifice, the command to eat His Body and drink His Blood is the necessary fulfillment of the Passover pattern, not an optional symbol. Just as the Israelites had to eat the lamb to participate in the covenant of deliverance, so we must eat Christ's flesh to participate in the New Covenant of eternal salvation.

Josefa de Ayala, The Sacrificial Lamb (c. 1670-1684)

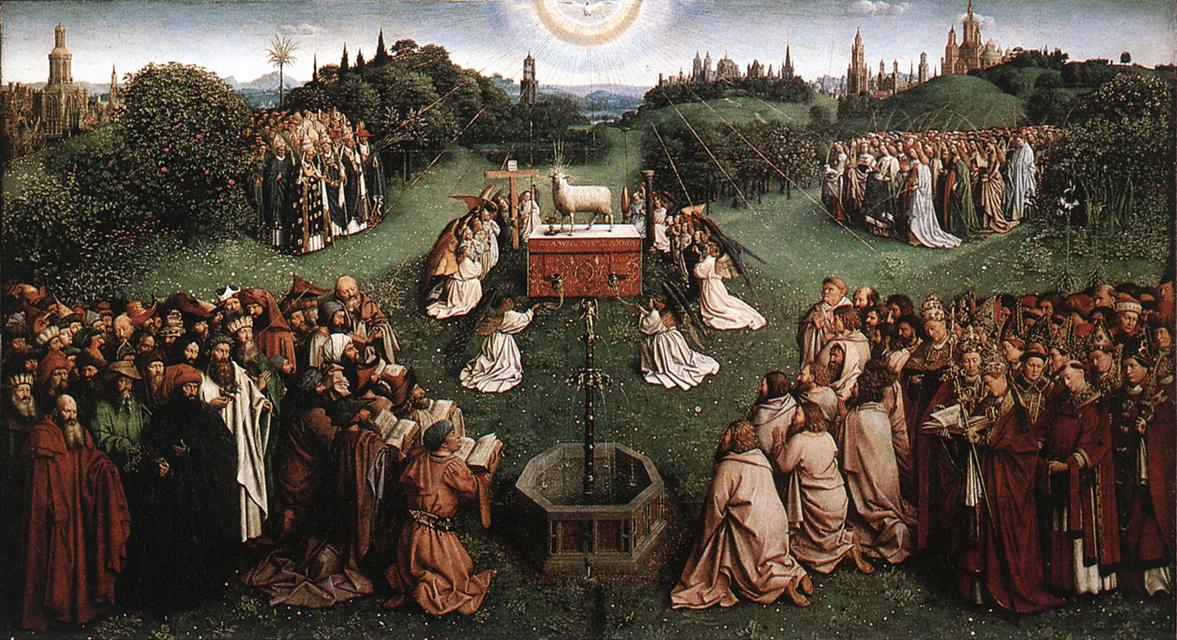

Jan van Eyck, Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (from the Ghent Altarpiece, 1432)

Pietro Lorenzetti, Crucifixion (c. 1340)

The Promise: John Chapter 6

_by_James_Tissot.jpg)

James Tissot, The Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes (c. 1886-1896), Brooklyn Museum

Paolo Veronese, The Wedding at Cana (1563), Louvre Museum, Paris

The Liturgical Stage: Passover, Manna, and New Exodus

"Now the Passover, the feast of the Jews, was at hand." — John 6:4

John deliberately sets the stage by noting the proximity of Passover. This is the interpretive key— everything Jesus says must be understood in light of the central salvific event of Israel's history: deliverance through the blood of the lamb and the manna in the wilderness.

The Bread of Life Discourse: From Metaphor to Scandal

Phase 1: The Spiritual Metaphor (vv. 35-50)

"I am the bread of life; whoever comes to me shall never hunger, and whoever believes in me shall never thirst." — John 6:35

Initially, Jesus uses language that can be understood metaphorically. "Coming to" and "believing in" Him are spiritual acts. The audience grumbles, but not about eating His flesh—they object to His claim to have come down from heaven.

Phase 2: The Shocking Turn (v. 51c)

"...and the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh." — John 6:51

Here the discourse pivots dramatically. Jesus moves from "I am the bread" (identity) to "the bread... is my flesh" (institution). He uses the Greek word sarx—flesh—the same word John used for the Incarnation: "The Word became flesh" (John 1:14).

The Crowd's Response: "The Jews then disputed among themselves, saying, 'How can this man give us his flesh to eat?'" (John 6:52)

Their question reveals literal understanding: not "What does this metaphor mean?" but "How is this physically possible?" They're horrified because they understand Him literally.

Phase 3: The Intensification (vv. 53-58)

"Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you... For my flesh is true food, and my blood is true drink." — John 6:53, 55

When confronted with their literal objection, Jesus doesn't clarify a misunderstanding. Instead, He escalates with:

- A solemn oath: "Truly, truly" (Amen, amen)

- An absolute requirement: "unless you eat... you have no life"

- Addition of drinking His blood—deeply offensive to Jews who were forbidden to consume blood

- Declaration: "my flesh is TRUE (alēthēs) food"—meaning real, actual, not figurative

The Linguistic Proof: From Phagein to Trōgein

Perhaps the most compelling evidence lies in the original Greek. When the crowd objects, Jesus makes a deliberate change in vocabulary:

| Before v. 52 | After v. 52 |

|---|---|

| phagein (φαγεῖν) | trōgein (τρώγειν) |

| Common verb "to eat" | "To gnaw, chew, crunch" |

| Can be metaphorical | Visceral, physical, graphic |

| Used for general eating | Often describes how animals eat |

Why This Matters: A teacher whose metaphor has been misunderstood would use softer, more abstract language to clarify. Jesus does the opposite—He switches to a more graphic, undeniably physical verb. This is deliberate intensification, not clarification. He's removing ambiguity, not creating it.

The Great Defection and the Test of Faith

"After this many of his disciples turned back and no longer walked with him." — John 6:66

The consequence is immediate and tragic. Not just skeptics, but committed disciples abandon Jesus over this "hard saying" (John 6:60). This mass departure is unprecedented in the Gospels.

The Uncorrected Misunderstanding: Elsewhere, when disciples misunderstand a metaphor, Jesus clarifies (John 4:32-34 about "food"; Matthew 16:11-12 about "leaven"). Here, facing a massive defection, He offers no clarification. Instead, He turns to the Twelve: "Do you also want to go away?" (John 6:67).

Peter's response reveals the nature of true faith: "Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life" (John 6:68). He doesn't claim to understand how it's possible—he submits because of who is teaching it. The Real Presence becomes a test of faith in Christ's person and authority.

Addressing John 6:63: "The flesh is of no avail"

"It is the Spirit that gives life; the flesh is of no avail. The words that I have spoken to you are spirit and life." — John 6:63

This is the primary objection to the Real Presence from John 6. Critics argue Jesus is saying His previous literal language was wrong—that "the flesh" profits nothing.

The Refutation:

- Internal Contradiction: Jesus cannot say His flesh is true food (v. 55) and then say His flesh profits nothing (v. 63). That would make Him incoherent.

- Biblical Usage of "Flesh vs. Spirit": Throughout Scripture (especially John and Paul), "flesh" doesn't mean "literal" versus "symbolic." It means the fallen, natural human perspective versus the supernatural, grace-filled perspective. "You judge according to the flesh" (John 8:15) means judging by worldly standards.

- The Diagnosis: Jesus is explaining why they can't accept His teaching—they're understanding it "according to the flesh" (carnally, naturalistically) rather than "according to the Spirit" (by supernatural faith). The verse explains the requirement for acceptance, not the nature of the teaching.

His words are "spirit and life" not because they're symbolic, but because they're divine truths that require the Holy Spirit's grace to believe. This verse actually reinforces the supernatural character of the Real Presence.

The Institution: The Last Supper

The Passover Context

The Last Supper occurs during the Passover meal—the annual commemoration of Israel's deliverance. Significantly, the Gospel accounts mention no lamb on the table. Jesus Himself is the Lamb whose sacrifice is being initiated.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper (c. 1495-1498)

Juan de Juanes, The Last Supper (16th century)

Tintoretto, The Last Supper (1592-1594), Basilica of San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice

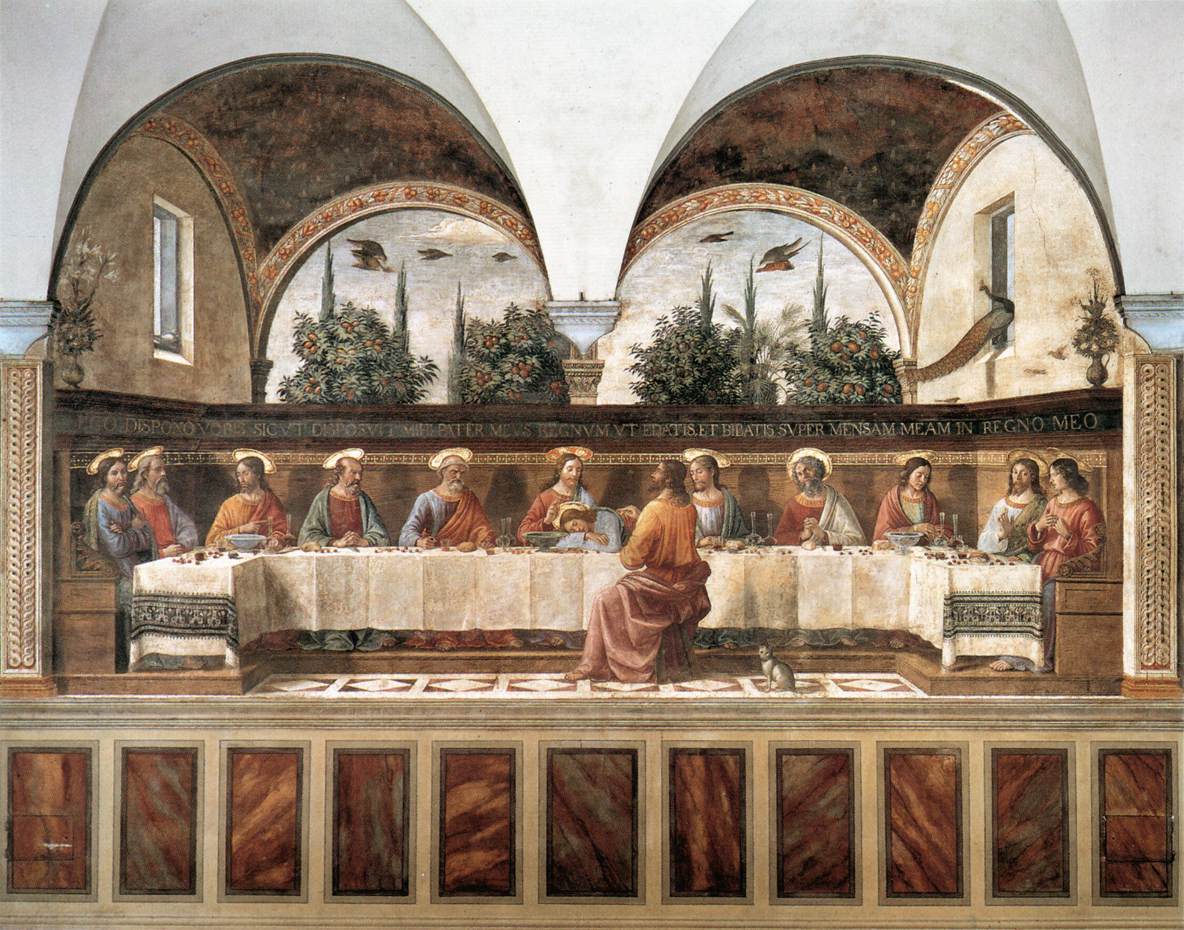

Domenico Ghirlandaio, The Last Supper (1480), San Marco, Florence

Jacopo Bassano, The Last Supper (1542)

"This IS My Body": The Words of Institution

"And he took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and gave it to them, saying, 'This is my body, which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me.' And likewise the cup after they had eaten, saying, 'This cup that is poured out for you is the new covenant in my blood.'" — Luke 22:19-20

The Greek Text: Touto Estin To Soma Mou

The Greek phrase is remarkably consistent across all four accounts (Matthew, Mark, Luke, 1 Corinthians):

τοῦτό ἐστιν τὸ σῶμά μου

touto estin to sōma mou

"This IS my body"

Why "IS" Means "IS"

The verb estin is a copula—its primary meaning is identity, not representation. To read it as "represents" or "symbolizes" requires:

- Changing the verb to a different word entirely

- Altering the grammatical structure

- Imposing a meaning not present in the text

How This Differs from Clear Metaphors

| Feature | Eucharistic Statements | "I Am" Metaphors |

|---|---|---|

| Statement | "This is my body" | "I am the door" / "I am the vine" |

| Context | Solemn covenant meal; Passover fulfillment | Teaching discourse or parable |

| Clarity | Clear predication of identity | Obvious metaphor (Jesus isn't wooden or plant) |

| Response | Disciples obey; no confusion recorded | Sometimes confusion, always explained |

"The Blood of the New Covenant"

"This cup that is poured out for you is the new covenant in my blood." — Luke 22:20

Jesus directly echoes Moses establishing the Old Covenant: "Behold the blood of the covenant" (Exodus 24:8). In Jewish thought, blood is the sign and seal of covenant—it creates family bonds with God.

The Old Testament prohibition against drinking blood was absolute. By commanding His disciples to drink His blood, Jesus isn't using a careless metaphor—He's instituting a new and superior covenant that requires partaking of His divine life itself. To reduce this to "believing in His sacrifice" misses the covenantal, familial, and incarnational depth of the command.

The Church Fathers: Apostolic Witness to the Real Presence

The testimony of the early Church Fathers is crucial: these were men who learned directly from the Apostles or their immediate successors. Their unanimous witness to the Real Presence demonstrates this wasn't a medieval invention but the original, apostolic faith.

Jan van Kessel the Elder, The Eucharist (c. 1626-1679)

St. Ignatius of Antioch

Bishop of Antioch, disciple of the Apostle John, martyred in Rome

"They abstain from the Eucharist and from prayer because they do not confess that the Eucharist is the flesh of our Savior Jesus Christ, flesh which suffered for our sins and which the Father, in his goodness, raised up again."— Letter to the Smyrnaeans 7:1

Analysis: Ignatius links denial of the Real Presence directly to the heresy of Docetism (the belief Christ only appeared to have a body). For him, the reality of Christ's flesh in the Eucharist is inseparable from the reality of the Incarnation. To deny one is to deny the other.

"I desire the bread of God, which is the flesh of Jesus Christ... and for drink I desire his blood, which is love incorruptible."— Letter to the Romans 7:3

St. Justin Martyr

Philosopher and apologist, wrote to the Roman Emperor

"This food we call Eucharist, of which no one is allowed to partake except one who believes that the things we teach are true, and has received the washing for forgiveness of sins and for rebirth, and who lives as Christ handed down to us. For we do not receive these things as common bread or common drink; but as Jesus Christ our Saviour being incarnate by God's word took flesh and blood for our salvation, so also we have been taught that the food consecrated by the word of prayer which comes from him, from which our flesh and blood are nourished by transformation, is the flesh and blood of that incarnate Jesus. For the apostles in the memoirs composed by them, which are called Gospels, thus handed down what was commanded them: that Jesus, taking bread and having given thanks, said, 'Do this for my memorial, this is my body'; and likewise taking the cup and giving thanks he said, 'This is my blood'; and gave it to them alone."— First Apology 66

Analysis: Justin Martyr provides crucial evidence linking apostolic tradition directly to Real Presence belief. Writing around 155 AD—just 60 years after John's Gospel—he establishes several critical points: First, restricted communion requiring baptism and faithful Christian living demonstrates the Church's understanding that this is not mere bread but Christ Himself. Second, his explicit rejection of "common bread or common drink" leaves no room for symbolic interpretation. Third, the parallel he draws between the Incarnation (the Word became flesh) and the Eucharist (food becomes Christ's flesh) shows the Church understood both as real transformations, not metaphors. Finally, his appeal to "the memoirs composed by [the apostles], which are called Gospels" proves this doctrine came directly from apostolic teaching, not later innovation. The transformation happens "by the word of prayer"—the consecratory formula—and results in food that is truly "the flesh and blood of that incarnate Jesus."

St. Irenaeus of Lyons

Disciple of St. Polycarp (who learned from John)

"When, therefore, the mixed cup and the baked bread receives the Word of God and becomes the Eucharist, the body of Christ, and from these the substance of our flesh is increased and supported, how can they say that the flesh is not capable of receiving the gift of God, which is eternal life?"— Against Heresies 5.2.3

Analysis: Irenaeus uses the Eucharist to refute Gnosticism. His argument: if our physical bodies are nourished by the physical Body of Christ, then matter isn't evil and our bodies are destined for resurrection. The Real Presence guarantees bodily resurrection.

Origen of Alexandria

Scholar and theologian

"You who are wont to be present at the divine mysteries, know how, when you receive the body of the Lord, you preserve it with all care and veneration, lest the smallest particle of it should fall, lest a crumb fall from thee of what is more precious than gold and precious stones."— Homilies on Exodus 13:3

Analysis: Origen testifies to universal practice—extreme care for every particle. This reverence makes sense only if every fragment contains the whole Christ. This is implicit adoration long before the term was formally defined.

St. Cyprian of Carthage

Bishop of Carthage, martyr, confronting the crisis of the lapsi (Christians who denied Christ under persecution)

"He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life. Therefore the Eucharist is our life."— St. Cyprian, On the Lapsed 16

Context of the Lapsi Crisis: During the Decian persecution (250-251 AD), many Christians denied Christ under threat of death. When these lapsi ("fallen ones") sought readmission to the Church, a critical question arose: Should they be allowed to receive the Eucharist immediately, or must they undergo penance first? Cyprian's answer reveals his profound belief in the Real Presence.

"Do not think, dearest brother, that either the courage of the brethren will be lessened, or that martyrdoms will fail for this cause, that penance is relaxed to the lapsed, and that the hope of peace is offered to the penitent... Some of the lapsed, either voluntarily or on being exhorted by us, have not withdrawn from the Church... I am preserving them entire for thy sentence."— St. Cyprian, Epistle 10

Unworthy Communion as Sacrilege: Cyprian insists the lapsi must undergo lengthy penance before receiving communion again. Why such severity? Because he understood the Eucharist as the actual Body and Blood of Christ—to receive unworthily was to commit a new act of violence against the Lord.

"They do violence to his body and blood, a sin more heinous against the Lord with their hands and mouths than when they denied him."— St. Cyprian, On the Lapsed 16

Analysis: This is extraordinary. Cyprian declares that unworthy reception of the Eucharist is worse than apostasy itself—worse than denying Christ under threat of death. This makes sense only if the Eucharist is truly Christ's Body and Blood. To approach His flesh with defiled hands and mouths is to crucify Him again, to do violence to His very body.

Notice Cyprian's consistent appeal to John 6:53: "He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood." For him, this verse is the key to understanding both the necessity and the danger of the Eucharist. It grants eternal life to the worthy, but condemns the unworthy to an even graver sin than apostasy.

"For how can he who is himself unclean cleanse another? Or how can he who has lost the Holy Spirit himself grant the Holy Spirit to another? Wherefore, with prayers and fasting, let us beg and entreat the Lord, who is both merciful and patient, that, as He has condescended to number us among His people, He may also be pleased to restore to us His grace."— St. Cyprian, Epistle 69

Eucharist as Test of Communion: Throughout the crisis, Cyprian used the Eucharist as the acid test of true communion with Christ. The lapsi could attend services and pray, but they could not receive communion until properly reconciled. The Eucharist wasn't a symbol of membership—it was union with Christ Himself, reserved only for those in a state of grace.

St. Cyril of Jerusalem

Bishop, taught catechumens preparing for baptism

"Do not, therefore, regard the bread and wine as simply that; for they are, according to the Master's declaration, the body and blood of Christ. Even though the senses suggest to you the other, let faith make you firm."— Mystagogical Catechesis 4:6

"Having learnt these things, and been fully assured that the seeming bread is not bread, though sensible to taste, but the Body of Christ; and that the seeming wine is not wine, though the taste will have it so, but the Blood of Christ... strengthen your heart."— Mystagogical Catechesis 4:9

Analysis: Cyril explicitly teaches the distinction between appearance (what senses perceive) and reality (what faith knows). This is the conceptual foundation for transubstantiation centuries before the philosophical terminology was developed.

St. Ambrose of Milan

Bishop, influential Western Father

"But if the word of Elijah had such power as to bring down fire from heaven, shall not the word of Christ have power to change the nature of the elements? You may perhaps say: 'My bread is ordinary.' But that bread is bread before the words of the Sacraments; where the consecration has entered in, the bread becomes the flesh of Christ."— On the Mysteries 9:52

Analysis: Ambrose explicitly teaches transformation of nature (natura) through the words of consecration. The same divine word that creates ex nihilo can certainly transform existing substances. This is direct preparation for transubstantiation theology.

St. Augustine of Hippo

Greatest Western Father, Doctor of the Church

"[Christ] received earth from earth; because flesh is from the earth, and He took flesh from the flesh of Mary. He walked here in the same flesh, and gave us the same flesh to be eaten unto salvation. But no one eats that flesh unless he first adores it... and not only do we not sin by adoring, we do sin by not adoring."— Explanations of the Psalms 98:9

Analysis: This is the first explicit theological justification for Eucharistic adoration. Augustine declares it's not merely permitted but obligatory to adore the Eucharist before receiving. Why? Because it's the flesh of Christ, and Christ is God.

"That bread which you see on the altar, having been sanctified by the Word of God, is the body of Christ. That chalice, or rather, what is in that chalice, having been sanctified by the Word of God, is the blood of Christ."— Sermons 227

St. John Chrysostom

"Golden-mouthed" preacher, Patriarch of Constantinople

"Let us stir ourselves and be filled with horror. This is the body that he has given to us to hold and to eat!... In order then that we may become one Body not only in love but in lived reality, let us be blended into that flesh."— Homilies on John 46:3

"This Blood, worthily received, drives away devils and keeps them far away from us, while it calls to us Angels and the Lord of Angels. This Blood, poured forth, washed clean all the world."— Homilies on John 46:3

Analysis: Chrysostom's vivid, almost shocking language expresses profound realism. The Eucharist creates not just spiritual but physical unity with Christ—our flesh is "blended" with His. This is visceral, incarnational theology.

St. John of Damascus

Last of the great Eastern Fathers

"The bread and the wine are not merely figures of the body and blood of Christ (God forbid!) but the deified body of the Lord itself: for the Lord has said, 'This is my Body,' not 'This is a figure of my body'; and 'my Blood,' not 'a figure of my blood.'"— Exposition of the Orthodox Faith 4:13

"The bread itself and the wine are changed into God's body and blood. But if you inquire how this happens, it is enough to learn that it was through the Holy Spirit... and we know nothing further save that the Word of God is true and energizes and is omnipotent, but the manner of this cannot be searched out."— Exposition of the Orthodox Faith 4:13

Analysis: John of Damascus, writing in the 8th century, explicitly rejects symbolic interpretations and affirms real change through the Holy Spirit. He acknowledges the mystery—we know that it changes, but the how transcends human understanding.

The Patristic Consensus

From the immediate disciples of the Apostles through eight centuries of Church teaching, we find:

- Universal Testimony: Not a single Church Father teaches a merely symbolic view

- Liturgical Practice: Extreme reverence for particles, reservation for the sick, careful handling—all indicating belief in real presence

- Theological Development: From simple assertion to sophisticated explanation, but always affirming the same reality

- Defense of Orthodoxy: The Real Presence used to defend the Incarnation against heresy (Ignatius vs. Docetism, Irenaeus vs. Gnosticism)

- Foundation for Adoration: Augustine's explicit command to adore before consuming

The Question for Protestants: If the "symbolic view" is correct, where is it in the first 1,500 years of Christianity? The burden of proof lies with those claiming the entire early Church was wrong about the central act of Christian worship.

Reservation Practices: Belief in the Abiding Presence

The early Church's practice of reserving the consecrated Eucharist—setting it aside after the liturgy for later use—provides powerful testimony to belief in the Real and abiding Presence of Christ. These practices reveal that the Church believed Christ remained present in the elements even after the liturgical celebration concluded.

The Pastoral Origin: Communion for the Absent

Reservation didn't begin as a devotional practice but arose from pastoral charity—the desire to bring communion to those who couldn't attend the liturgy: the sick, the dying, the imprisoned, and those unable to travel.

St. Justin Martyr (c. 155 AD): Deacons Carry the Eucharist

First detailed account of the Mass, written to the Roman Emperor

"When the president has given thanks and the people have assented, those whom we call deacons give to each of those present a portion of the consecrated bread and wine and water, and they take it to those who are absent."— St. Justin Martyr, First Apology 67

Theological Significance: This is the earliest explicit documentary evidence for reservation. The practice would be theologically incoherent if Christ's presence were believed to be confined only to the moment of liturgical action or immediate reception. The fact that deacons carried the Eucharist away from the assembly demonstrates belief that the consecrated elements remained the Body and Blood of Christ after the liturgy concluded. This simple pastoral provision contains a profound doctrinal affirmation: the Real Presence abides.

Tertullian (c. 210 AD): Home Reservation During Persecution

North African theologian during the age of persecution

"The faithful know well the practice of taking part in the sacrifice before eating, and partaking (accepto) of the Body of the Lord and reserving it (et reservato)."— Tertullian, Ad Uxorem 2:5Tertullian provides crucial evidence for domestic reservation—the practice of Christians taking the Eucharist to their homes for private communion. This was particularly common on "station days" (days of fasting) when public liturgy might not be celebrated.

"Will your husband not know what it is which you secretly eat of before (taking) any food? And if he knows it to be bread, then what will he think of you in his arrogance?"— Tertullian, Ad Uxorem 2:5Historical Context: In this passage, Tertullian warns a Christian widow against marrying a pagan, highlighting the practical difficulty it would pose for her Eucharistic devotion. The pagan husband would notice her eating "bread" before any other food and question the practice. This confirms not only home reservation but also self-communication by the laity—a necessity born of persecution.

St. Cyprian of Carthage (c. 251 AD): The Casket of Fire

Bishop during Decian persecution, addressing the crisis of the lapsi

"Another woman, when she tried to open her box (arca), in which was the holy (body) of the Lord, with unworthy hands, fire rising from it deterred her from daring to touch it."— St. Cyprian, On the Lapsed 26

Cyprian recounts miraculous divine judgments upon those who approached the reserved sacrament unworthily. One woman kept the Eucharist in a personal chest or casket (arca) at home. When she attempted to open it with "polluted hands" (having apostatized during persecution), flames burst forth, preventing her from touching the sacred species.

"Another man who had secretly received communion while in a state of serious sin could not eat nor handle the holy of the Lord; but he found in his hands when opened that he had a cinder."— St. Cyprian, On the Lapsed 26

Theological Implications: Whether understood as literal history or powerful pastoral warnings, these narratives communicate vital truths:

- Objective Reality: The Eucharist is an objective, powerful reality—not a passive symbol

- Moral Requirement: Approaching unworthily brings judgment, not just symbolic disrespect

- Abiding Holiness: The reserved Sacrament retains its sacred power and requires purity of heart

- Home Preservation: The practice of domestic reservation was widespread enough to be assumed in these warnings

Cyprian's Conclusion: He explicitly declares that unworthy reception is violence against Christ Himself: "They do violence to his body and blood, a sin more heinous against the Lord with their hands and mouths than when they denied him" (On the Lapsed 15-16). The Eucharist isn't just a sign of Christ—it is Christ, and to profane it is to assault the Lord directly.

St. Basil the Great (c. 379 AD): The Golden Dove

Cappadocian Father, Bishop of Caesarea

St. Basil's biography records a significant development in reservation practice. When celebrating the liturgy, he would divide the consecrated Bread into three parts:

- One part he consumed himself

- One part he distributed to the monks

- The third he placed in a golden container shaped like a dove (peristerium), which was suspended over the altar

Historical Significance: This marks a crucial transition:

- From Private to Public: Reservation shifts from hidden necessity (home storage during persecution) to honored visibility within the church

- From Utilitarian to Devotional: While still practical (for communion of the sick), the golden dove and prominent placement signal reverence beyond mere convenience

- Symbolic Richness: The dove, symbol of the Holy Spirit, hovering over the altar creates powerful visual theology—the Spirit overshadows the sacred elements just as He overshadowed Mary at the Annunciation

- Foundation for Adoration: Honored, visible reservation within the sanctuary naturally leads to direct veneration and worship

The Peristerium Tradition: This vessel—the golden dove suspended over the altar— became common in both East and West. Medieval churches often had elaborate dove-shaped tabernacles. The practice demonstrates that well before formal definitions, the Church was already housing Christ as an honored king in His temple.

From Necessity to Devotion: The Arc of Development

| Period | Practice | Primary Location | Primary Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100-313 AD Persecution | Home reservation by faithful | Private homes, personal caskets | Self-communion, communion of sick |

| 313-500 AD Legalization | Shift to church reservation | Sacristy, locked rooms (pastoforium) | Viaticum for dying, communion of sick |

| 500-1000 AD Honored Presence | Visible sanctuary reservation | Golden dove (peristerium) over altar | Practical need + emerging devotion |

| 1000+ AD Devotional Focus | Tabernacle, exposition, adoration | Prominent tabernacle on/near altar | Worship, adoration, Benediction |

What Reservation Proves About Belief

The consistent practice of reservation across centuries and diverse circumstances provides irrefutable evidence of the Church's unwavering belief in the Real and abiding Presence:

- If Merely Symbolic: Why reserve blessed bread? Ordinary bread could serve any symbolic purpose.

- If Presence Temporary: Why take it to the absent if Christ's presence expired after the liturgy?

- If Just Memorial: Why such elaborate vessels and honored placement?

- If No Real Presence: Why would unworthy approach bring divine judgment?

The Logic is Inescapable: The Church reserved the Eucharist because it believed the Eucharist was—and remained—Christ Himself. From Justin's deacons in the second century to Basil's golden dove in the fourth, from Tertullian's domestic practice to Cyprian's caskets of fire, one belief unifies all these practices: Christ abides in the consecrated species. This abiding presence is the necessary foundation for any later development of Eucharistic adoration, which St. Augustine would explicitly command: "No one eats that flesh unless he first adores it."

The Doctrine of Transubstantiation

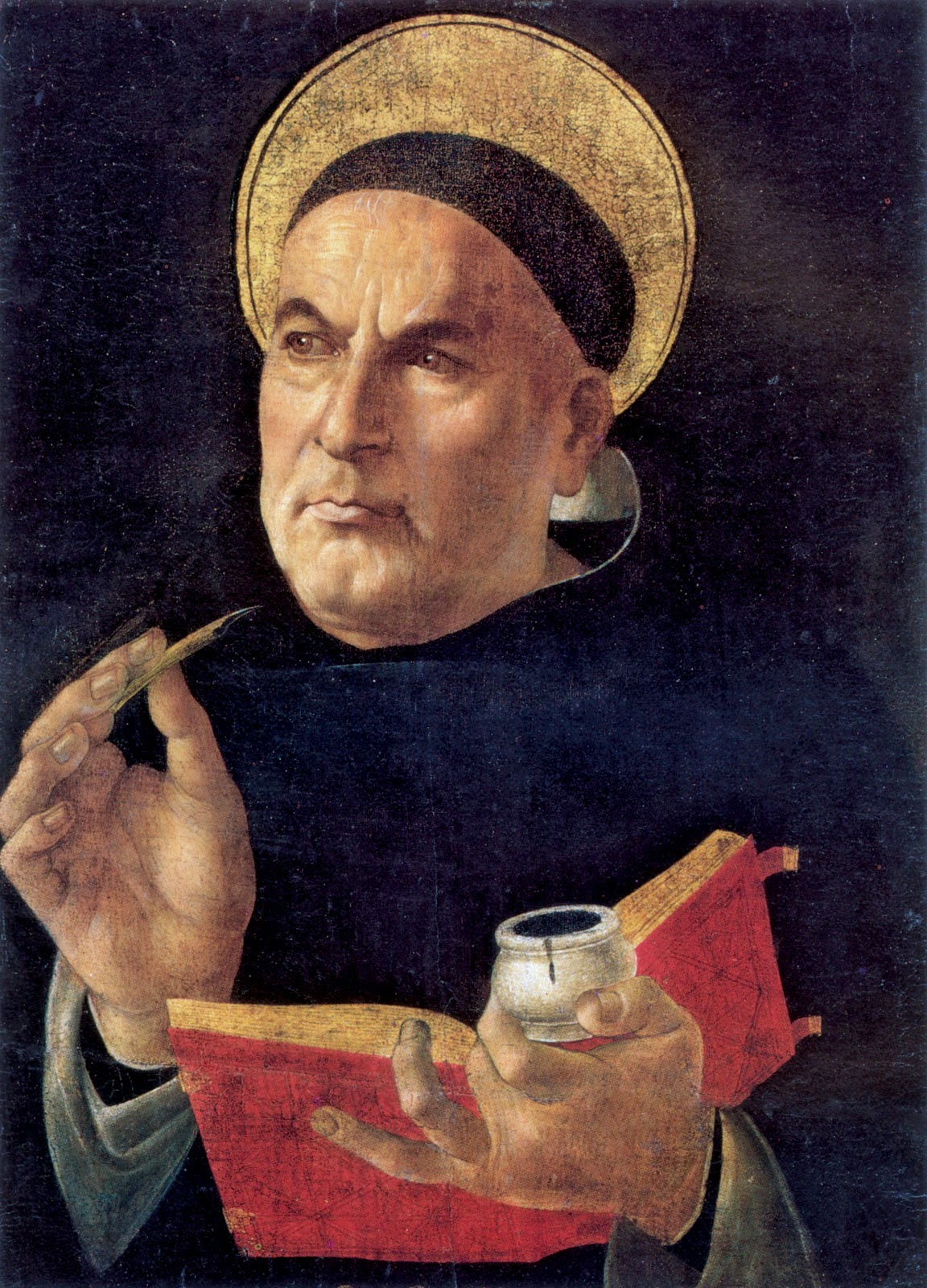

Sandro Botticelli, St. Thomas Aquinas (c. 1481)

What Is Transubstantiation?

Transubstantiation is the theological term, formally defined at the Fourth Lateran Council (1215 AD), that explains how Christ is really present in the Eucharist.

The Definition

"The change of the whole substance of bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and of the whole substance of wine into the substance of the Blood of Christ. This change has been fittingly and properly called transubstantiation."— Council of Trent, Session 13

Understanding Substance and Accidents

The doctrine uses Aristotelian philosophical categories to explain the mystery:

Substance

The underlying reality of what something IS—its essential nature, what makes it what it is. This is not visible or measurable.

Example: The "dogness" that makes a dog a dog, not a cat.

Accidents

The observable properties—appearance, taste, texture, chemical composition, weight. These are what our senses perceive.

Example: The dog's color, size, breed characteristics.

What Changes at Consecration

| Aspect | Before Consecration | After Consecration |

|---|---|---|

| Substance (What it IS) | Bread and Wine | Body and Blood of Christ |

| Accidents (What it appears to be) | Looks, tastes, smells like bread and wine | Still looks, tastes, smells like bread and wine |

| Reality | Common food | Christ Himself—Body, Blood, Soul, Divinity |

Why This Terminology?

- To Explain Christ's Words: When Jesus says "This IS my body," transubstantiation explains how something can truly be His body while appearing as bread.

- To Avoid Two Errors:

- Mere Symbolism: Reduces "is" to "represents"—denies the Real Presence

- Gross Materialism: Imagines crude, cannibalistic consumption—misunderstands the sacramental mode of presence

- To Safeguard the Mystery: Acknowledges what changes (substance) while explaining why we don't see the change (accidents remain).

- To Answer John 6's "How?": The crowd asked, "How can this man give us his flesh to eat?" Transubstantiation answers: through a substantial change that transcends physical laws.

Not an Invention, but a Development

Critics claim transubstantiation is a "medieval invention." But consider the evidence:

| Century | What the Church Believed | What the Church Said |

|---|---|---|

| 1st-2nd | Real Presence | "The Eucharist is the flesh of Christ" (Ignatius) |

| 4th | Real Presence through change | "The bread becomes the flesh of Christ" (Ambrose) |

| 4th | Appearance vs. Reality | "The seeming bread is not bread... though sensible to taste" (Cyril) |

| 8th | Substance changes | "The bread and wine are changed into God's body and blood" (John Damascene) |

| 13th | Same belief, precise language | "Transubstantiation" formally defined (Lateran IV, 1215) |

The Pattern of Development: The doctrine doesn't change—the reality believed is the same from Ignatius to Lateran IV. What develops is the theological precision and philosophical vocabulary to defend and explain what was always believed. This is organic development, not innovation.

The Deeper Meaning

Transubstantiation isn't just philosophical precision—it's profoundly biblical:

- It Fulfills John 6: "My flesh is TRUE (alēthēs—real, actual) food" demands more than symbolism

- It Honors Christ's Words: "This IS" means substantial identity, not representation

- It Completes the Incarnation: The Word became flesh (John 1:14); that flesh becomes our food (John 6:51)

- It Makes Possible Real Union: "He who eats my flesh... abides in me" (John 6:56) requires real presence for real union

- It Explains Paul's Warning: "Guilty of profaning the body and blood" (1 Corinthians 11:27) makes sense only if the body and blood are really present to be profaned

Historical Timeline: From Promise to Definition

c. 30 AD: The Institution

Last Supper: Jesus institutes the Eucharist at the Passover meal

John 6: The Bread of Life discourse promises the gift

Acts 2:42: "They devoted themselves to... the breaking of bread"

50-100 AD: Apostolic Practice

1 Corinthians 10-11 (c. 55 AD): Paul's teaching on the Real Presence and unworthy reception

Didache (c. 70-90 AD): Early liturgical instructions for the Eucharist

100-325 AD: Early Fathers Defend the Faith

- Ignatius (110 AD): Links Real Presence to Incarnation against Docetism

- Justin Martyr (155 AD): First detailed Mass description; Incarnational analogy

- Irenaeus (189 AD): Uses Eucharist to defend resurrection of the body

- Tertullian (210 AD): Evidence for home reservation

- Origen (248 AD): Extreme care for particles

- Cyprian (251 AD): Eucharist as test of communion

325-600 AD: Golden Age of Doctrinal Clarity

- Cyril of Jerusalem (350 AD): Appearance vs. reality distinction

- Basil the Great (379 AD): Golden dove for reservation

- Ambrose (390 AD): Change of nature (natura) through consecration

- Augustine (412 AD): Command to adore before receiving

- John Chrysostom (400 AD): Visceral, physical union with Christ

600-1000 AD: Liturgical Development

- Gregory the Great (604 AD): Mass as unbloody sacrifice

- John of Damascus (749 AD): Explicit rejection of symbolism

- Paschasius Radbertus (9th c.): First systematic treatise on Eucharist

1215 AD: Fourth Lateran Council

Formal Definition of Transubstantiation

"There is one Universal Church of the faithful, outside of which there is absolutely no salvation. In which there is the same priest and sacrifice, Jesus Christ, whose body and blood are truly contained in the sacrament of the altar under the forms of bread and wine; the bread being changed (transubstantiatis) by divine power into the body, and the wine into the blood, so that to realize the mystery of unity we may receive of Him what He has received of us."Significance: After 1,200 years of consistent belief and practice, the Church employs philosophical precision to formally define the teaching. This doesn't create new doctrine— it guards ancient faith with precise language.

1215-1517: Eucharistic Devotion Flourishes

Following the Fourth Lateran Council's formal definition of transubstantiation, the medieval Church experienced an unprecedented flowering of Eucharistic devotion. This wasn't the creation of a new doctrine, but the natural outpouring of love and adoration for the Real Presence that had always been believed.

St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274)

The greatest theologian of the medieval period devoted much of his scholarly work to articulating and defending the Real Presence. His contributions include:

- Summa Theologica (1266-1273): Provides the most comprehensive philosophical and theological explanation of transubstantiation using Aristotelian categories of substance and accidents. Thomas explains how Christ's Body and Blood become truly present while the appearances of bread and wine remain.

- Pange Lingua (1264): Composed this sublime Eucharistic hymn at Pope Urban IV's request for the new Feast of Corpus Christi. The final two stanzas, "Tantum Ergo," remain one of the Church's most beloved hymns of adoration.

- Adoro Te Devote: A deeply personal prayer expressing faith in Christ's hidden presence: "Seeing, touching, tasting are in thee deceived; How says trusty hearing? That shall be believed; What God's Son has told me, take for truth I do; Truth himself speaks truly or there's nothing true."

Feast of Corpus Christi (Established 1264)

Pope Urban IV established this universal feast day in response to a Eucharistic miracle at Bolsena (1263) and the visions of St. Juliana of Liège. The feast celebrates the Real Presence with:

- Solemn Processions: The Blessed Sacrament is carried through streets in a monstrance, allowing public adoration and demonstrating the Church's belief that Christ Himself is present in the consecrated Host.

- Liturgical Office: Thomas Aquinas composed the entire liturgy, including the sequence "Lauda Sion" and the hymns "Pange Lingua," "Sacris Solemniis," and "Verbum Supernum."

- Popular Devotion: The feast became one of the most elaborate celebrations in the Church's calendar, with entire cities participating in honoring Christ in the Eucharist.

Eucharistic Adoration Practices

The late medieval period saw the development and spread of devotional practices that could only make sense if the Real Presence were true:

- Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament: The practice of exposing the consecrated Host in a monstrance for public veneration, concluding with the priest blessing the people with the Sacrament itself. This demonstrates belief that Christ's presence continues beyond the Mass.

- Perpetual Adoration: Communities of religious (especially women) dedicated themselves to continuous prayer before the exposed Blessed Sacrament, believing they were literally keeping vigil before the living Christ.

- Tabernacle Devotion: Elaborate tabernacles were constructed to house the reserved Sacrament, with perpetual lamps burning to signify Christ's presence. Churches were left unlocked so the faithful could visit Christ at any hour.

- Eucharistic Miracles: Reports of visible manifestations—hosts bleeding, transforming into visible flesh—occurred across Europe. Whether or not one accepts specific miracle claims, their very existence proves the universal belief that the substance of Christ's Body was truly present.

The Significance: This explosion of Eucharistic devotion demonstrates that transubstantiation wasn't an abstract theological novelty imposed from above, but the formal articulation of what Christians had always believed and increasingly wanted to express through worship and devotion. You don't compose love songs to a symbol. You don't spend hours in adoration before a metaphor. These practices reveal the heart of medieval faith: the absolute conviction that Jesus Christ, true God and true man, is really, truly, and substantially present in the Eucharist.

1545-1563: Council of Trent

Reaffirmation Against Protestant Denials

The Protestant Reformation brought the first major challenge to the doctrine of the Real Presence in over a millennium. Various reformers proposed different understandings—from Luther's consubstantiation to Zwingli's pure symbolism. In response, the Council of Trent (1545-1563) solemnly reaffirmed the ancient faith.

What Trent Defined (Sessions 13 & 22)

Canon 1: "If anyone denies that in the sacrament of the most Holy Eucharist are contained truly, really and substantially the body and blood together with the soul and divinity of our Lord Jesus Christ, and consequently the whole Christ, but says that He is in it only as in a sign, or figure or force, let him be anathema."

- Real Presence: Christ is present "truly, really, and substantially"—not symbolically, not spiritually only, but in His full divine and human nature.

- Transubstantiation: The Council explicitly used this term, defining it as the conversion of the whole substance of bread into Christ's Body and the whole substance of wine into His Blood, while only the accidents (appearances) of bread and wine remain.

- Eucharistic Sacrifice: The Mass is not merely a memorial but a true propitiatory sacrifice, the same sacrifice as Calvary, re-presented (made present again) in an unbloody manner.

- Adoration: The Eucharist is to be adored with latria—the worship due to God alone—because Christ Himself is present. This directly refuted Protestant claims that Eucharistic adoration was idolatry.

- Reservation and Procession: The practice of reserving the Blessed Sacrament and carrying it in procession was defended as an ancient and laudable custom flowing from belief in the Real Presence.

Key Clarifications

Trent carefully explained what the Church had always taught:

- Whole Christ in Each Species: Christ is entirely present under the appearance of bread alone and entirely under the appearance of wine alone. The faithful receive the whole Christ even when receiving under one kind only.

- Permanence of Presence: Christ remains present as long as the Eucharistic species remain. The Real Presence doesn't depend on the moment of consumption or the faith of the recipient.

- Objective Reality: The Eucharist is Christ's Body and Blood because of the consecration and Christ's promise—not because of the recipient's faith or the minister's worthiness.

The Critical Point: Nothing New

Trent did not invent new doctrine. The Council fathers explicitly stated they were defining what had "always been believed" from the beginning. Every doctrine Trent proclaimed can be traced directly through the medieval theologians, back through the Church Fathers, to the Apostles themselves.

The Historical Reality: The evidence demonstrates that the Real Presence was not a late medieval innovation but the consistent, unbroken teaching from the beginning. The question was not "Is this in Scripture?" (the evidence clearly shows it is) but rather "Will we accept what Scripture and early Christian Tradition consistently teach?"

The Council of Trent's definitions represent the historic Christian understanding of the apostolic faith concerning the greatest of all mysteries: the Real Presence of Jesus Christ in the Eucharist.

Unity Then Division: The Reformation Challenge

For fifteen centuries—from the Apostles through the medieval period—the Christian Church maintained remarkable unity on the Real Presence. East and West, through schism and controversy, never disputed this central truth. The first major fracture came in the 16th century with the Protestant Reformation.

The Unbroken Consensus (30-1517 AD)

Despite countless theological debates over Christology, the Trinity, grace, and ecclesiology, no major Christian body before the 16th century denied the Real Presence:

- The Apostolic Fathers uniformly testified to Christ's true flesh and blood in the Eucharist

- The Great Schism (1054 AD) between Rome and Constantinople involved authority, the Filioque, and liturgical practices—but both sides affirmed the Real Presence and continue to do so today

- Medieval Heresies challenged papal authority, priestly celibacy, and Church corruption—but even the Waldensians, Albigensians, and pre-Reformation reformers like Wycliffe and Hus, despite their criticisms, did not universally deny transubstantiation

- East and West used different philosophical language (the East generally avoiding Aristotelian terminology), but both traditions celebrated the Divine Liturgy believing the bread and wine truly became the Body and Blood of Christ

The Significance: This remarkable consensus across fifteen centuries, multiple languages, diverse cultures, and even ecclesiastical division demonstrates that the Real Presence was not one theological opinion among many—it was the faith of the Church, believed everywhere, by everyone, always.

The 16th Century Shift: New Theological Starting Points

The Protestant Reformation brought the first systematic challenge to the Real Presence. This wasn't primarily a matter of discovering "new evidence" but rather applying different theological principles, especially Sola Scriptura (Scripture Alone), which led reformers to re-evaluate traditional doctrines.

1. Sola Scriptura vs. Philosophical Definition

Reformers like Huldrych Zwingli and John Calvin insisted all doctrine must be explicitly stated in Scripture, not derived from tradition or philosophy.

Their Argument: Transubstantiation relies on Aristotelian categories of "substance" and "accidents"—philosophical terms not found in Scripture. They viewed this as a "medieval invention" that obscured rather than clarified Christ's simple command to remember Him.

"Do this in remembrance of me." — Luke 22:19

The reformers shifted focus from a metaphysical change in the elements to the act of remembering and proclaiming Christ's finished work on the cross.

2. "Is" Means "Signifies"

At the Marburg Colloquy (1529), Zwingli famously debated Luther on the meaning of Christ's words of institution.

Zwingli's Position: The verb "is" (estin) in "This is my body" should be understood as "signifies" or "represents," just as in other biblical passages:

- "I am the vine" (John 15:5) — Jesus isn't literally a plant

- "The seed is the word of God" (Luke 8:11) — The seed represents the word

- "The seven heads are seven mountains" (Revelation 17:9) — Symbolic language

For Zwingli and Anabaptists, the bread and wine are symbols that direct believers' hearts toward Christ's sacrifice—a memorial and public profession of faith, not physical reception of Christ.

3. The Ascended Body of Christ

Both Zwingli and Calvin raised a Christological objection based on the Ascension:

"He sat down at the right hand of God... waiting until his enemies should be made a footstool for his feet." — Hebrews 10:12-13

Their Argument: Christ's true human body is in heaven, seated at the Father's right hand. A genuine human body must be localized—it cannot simultaneously be in heaven and physically present on thousands of altars on earth. To claim otherwise would:

- Deny the reality of Christ's human nature

- Confuse His human and divine natures (a form of Eutychianism)

- Attribute the divine quality of omnipresence to His human body

Calvin's Solution: Christ is truly present but remains bodily in heaven. During communion, the Holy Spirit "lifts up" the believer's soul through faith to heaven to spiritually feast on Christ. The presence is real but spiritual, not physical.

4. Reinterpreting John 6

The reformers inverted the Catholic interpretation of the Bread of Life discourse:

"It is the Spirit that gives life; the flesh is of no avail. The words that I have spoken to you are spirit and life." — John 6:63

Protestant Reading: This verse is the interpretive key to the entire chapter. Jesus deliberately corrected the crowd's "carnal, cannibalistic" misunderstanding. The "eating" He described is not physical consumption but the spiritual act of believing in Him.

Faith as the Mouth: For Calvin, "eating" Christ's flesh means believing in Him. The "food" is His atoning work, which the soul receives through faith alone. Physical eating of consecrated bread is merely the external sign of this interior, spiritual reality.

5. Rejection of Ex Opere Operato

The reformers universally rejected the doctrine that sacraments confer grace ex opere operato("by the work having been worked")—the teaching that the sacrament is effective through Christ's instituted action, regardless of the minister's worthiness.

Their Concern: This seemed to make the sacrament work "automatically," like magic, undermining Sola Fide (Faith Alone). They insisted:

- The benefits of communion are received only through personal faith

- Without faith, the participant receives only bread and wine, not Christ

- The believer's disposition is more critical than the minister's words of consecration

- The sacrament confirms and strengthens faith but doesn't create it or work independently of it

A Note on Martin Luther

It's important to note that Luther himself never denied the Real Presence. He fiercely defended it against Zwingli at Marburg, insisting Christ's words "This is my body" must be taken literally.

Luther's position, called Sacramental Union or sometimes Consubstantiation(though he disliked the term), taught that Christ's body and blood are present "in, with, and under" the bread and wine—truly present but without the substance of the bread and wine ceasing to exist.

Even Luther's affirmation of Real Presence, however, differed from the historic understanding by rejecting transubstantiation and the sacrificial nature of the Mass. His view represents a middle position but still marks a departure from the consistent teaching of the previous fifteen centuries.

The Catholic Response

The Council of Trent (1545-1563) responded to these Protestant challenges by solemnly reaffirming what the Church had always taught:

- Scripture and Tradition: The Church receives divine revelation from both Scripture and Sacred Tradition, with the Church's teaching authority (Magisterium) guided by the Holy Spirit to interpret both correctly.

- Literal Interpretation: Christ's words "This is my body" must be taken at face value, as the Church Fathers uniformly did. Philosophical terminology (like transubstantiation) doesn't add to Scripture but clarifies and defends what Scripture teaches.

- The Whole Christ: Christ can make Himself sacramentally present while remaining bodily in heaven because His mode of sacramental presence transcends physical laws. He is not "located" in the Host but truly, really, and substantially present under the appearances of bread and wine.

- John 6 Vindicated: The chapter cannot mean "believe in me" because Jesus already used "believe" earlier (v. 35) and then deliberately switched to the graphic language of eating and drinking (v. 53-56). The Spirit gives life precisely through the flesh of Christ that we consume.

- Grace and Faith: The sacrament is effective through Christ's promise and power, not human faith. However, to receive its benefits fruitfully, one must be in a state of grace and receive with faith and reverence. The sacrament doesn't work "magically"—it works because Christ instituted it and promised to work through it.

The Critical Question

The Reformation challenge forces us to ask: Does the unanimous testimony of the Church for fifteen centuries carry weight? When every Church Father, every ecumenical council before Trent, both Eastern and Western traditions, and the consistent practice of the faithful all agree—can we confidently set aside this witness based on a new theological system?

The Catholic Church answers: No. The faith "once for all delivered to the saints" (Jude 3) has been carefully guarded and faithfully transmitted. To accept the Reformation's reinterpretation would mean that the Holy Spirit allowed the entire Church—including those who learned directly from the Apostles—to fundamentally misunderstand the Eucharist for 1,500 years.

The Real Presence is not a "Roman Catholic invention" or a "medieval corruption." It is the apostolic faith, believed by the undivided Church, affirmed by the Fathers, celebrated in the liturgy, and now challenged for the first time in history. The question is not whether we will follow Scripture, but whether we will follow Scripture as the Church has always understood it, guided by the Holy Spirit through the centuries.

Conclusion: The Unbroken Thread

Caravaggio, Supper at Emmaus (1601)

From the Upper Room to the Fourth Lateran Council spans 1,185 years. Throughout this entire period, we find an unbroken thread of belief, practice, and devotion centered on one reality: in the Eucharist, Christ gives us His true Body and Blood.

The Weight of Evidence

- Old Testament Preparation: Melchizedek's bread and wine, the manna from heaven, the Bread of the Presence, and the Passover lamb all point forward to a supernatural food that must be consumed.

- John 6's Explicit Promise: Jesus's deliberate escalation from metaphor to stark literalism, His use of the graphic verb trōgein, and His refusal to clarify when disciples abandon Him—all indicate He meant exactly what He said.

- The Institution's Solemn Words: "This IS my body" in the context of Passover fulfillment and covenant-making cannot be reduced to symbolism without violence to the text.

- Apostolic Teaching: Paul's warning about profaning the body and blood, his teaching on koinonia (real participation), and the severe consequences of unworthy reception all demand real presence.

- Unanimous Patristic Witness: Not one Church Father in the first eight centuries teaches a merely symbolic view. All affirm, defend, and clarify the Real Presence in increasingly explicit terms.

- Liturgical Practice: The care for particles, reservation for the sick, instructions for reverent reception, and explicit commands to adore—all flow naturally from belief in real presence.

- Theological Development: From Ignatius's simple assertion to Lateran's philosophical precision is organic growth in understanding, not invention of new doctrine.

The Call to Faith

Like the disciples in John 6, we're presented with a teaching that transcends natural understanding. We can respond in three ways:

- Reject it as impossible (like the crowd in John 6:52)

- Find it too hard and walk away (like the disciples in John 6:66)

- Accept it through faith in Christ (like Peter in John 6:68-69)

"Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life. We have come to believe and to know that you are the Holy One of God."— John 6:68-69The Real Presence is not a peripheral doctrine but the beating heart of Christian worship. It's where heaven touches earth, where the Incarnation continues, where we are fed with the Bread of Life. Transubstantiation is simply the Church's careful explanation of what Christ promised and what the Church has always believed: "This is my body... This is my blood."

May this exploration of Scripture, Tradition, and reason lead us all to deeper faith in—and more profound reverence for—the Real Presence of our Lord in the Eucharist.

Further Reading

Recommended Book

- Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist by Brant Pitre — An excellent scholarly exploration of how Jewish Passover traditions illuminate Christ's institution of the Eucharist and the early Christian understanding of the Real Presence.

Primary Sources

The following primary sources are quoted throughout this treatise and provide direct testimony to the early Church's belief in the Real Presence:

- The Didache — The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles (c. 50-125 AD)

- St. Ignatius of Antioch — Letter to the Smyrnaeans and Letter to the Romans (c. 110 AD)

- St. Justin Martyr — First Apology (c. 155 AD)

- St. Irenaeus of Lyons — Against Heresies (c. 189 AD)

- Tertullian — On the Resurrection of the Flesh (c. 210 AD)

- Origen of Alexandria — Homilies on Exodus (c. 248 AD)

- St. Cyprian of Carthage — On the Lapsed and Epistles (c. 251 AD)

- St. Cyril of Jerusalem — Mystagogical Catecheses (c. 350 AD)

- St. Basil the Great — Letter to Caesaria (c. 372 AD)

- St. Ambrose of Milan — On the Mysteries (c. 390 AD)

- St. Augustine of Hippo — Explanations of the Psalms and Sermons (c. 400 AD)

- St. John Chrysostom — Homilies on John and Homilies on 1 Corinthians (c. 400 AD)

- St. John of Damascus — Exposition of the Orthodox Faith (c. 749 AD)